- Our School

- Our Advantage

- Admission

- Elementary•Middle School

- High School

- Summer

- Giving

- Parent Resources

- For Educators

- Alumni

« Back

Being an Efficient Homework Helper—Part III: Motivation and Tools

September 30th, 2019

By: Regina G. Richards

This is the third installment of a multi-part series about helping children manage homework. Thefirst post is about establishing good habits creating an optimal learning environment. The second postcovers homework strategies and dealing with fatigue. This article originally appeared in LDOnline.

Some children need external motivators to help maintain focus on the task. Some useful suggestions include homework contracts, devices to help monitor time on task, or rewards. It is important that you are setting realistic goals for your child and that they are not overly stressed in their area of a learning disability. Some children, for example, take longer to write by hand or to calculate sums so you need to be realistic about time allowed.

Contracts

Homework contracts may take many forms. Write the contract with your child, making sure it is within your child's ability level. Focus on one goal at a time. Examples follow.

- "I, Johnny, will complete my homework without argument for five nights in a row. When I accomplish this, I can watch 30 extra minutes of TV."

- "I, Susie, will mark off a square on my chart each night that I complete all my homework assignments. When I have marked off five squares, I will select a reward from my list."

The criteria in your contract should change as the child's skills change. Furthermore, it is important to be specific regarding your expectations regarding homework completion. Indicate definite starting and stopping points as well as minimum requirements.

Monitoring Time on Task

A timer is a useful device for monitoring time on task. It makes the passage of time more concrete for your child. Identify a reasonable time for your child to complete an assignment (or a given part) and set the timer to ring after that time. It is useful for your child to be able to observe the passage of time, on either the timer or hourglass. Example statements follow:

- "You have agreed to practice typing for five minutes every night. This means five minutes with good focus. I will set the timer and if you focus and practice appropriately the whole time, you will be done. Remember, I will have to restart the timer if you fool around in the middle."

- "You have a half-hour to complete this part of the assignment. I'm setting this timer for 30 minutes. If you finish your homework correctly by the time the bell goes off, then you will get X reward (or sticker)."

If your child is earning points or stickers for appropriate follow through, you may want to allow them to earn rewards for a given number of stickers. To phase out their dependence on the stickers, require a larger number of stickers for a reward as they becomes more responsible.

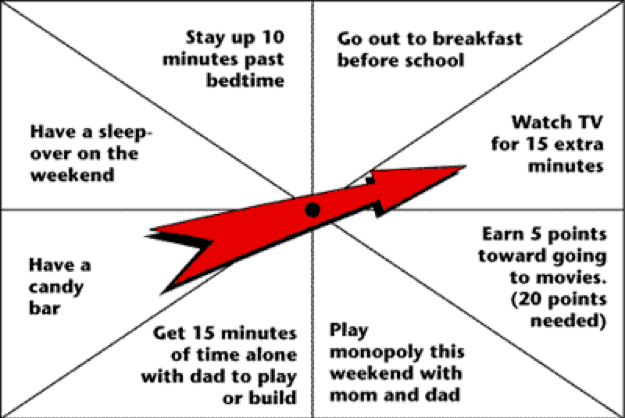

Spinner

Young children respond well to games as motivational aids. You can develop a customized game spinner by using cardboard and brads, or you may purchase blank spinners from an educational supply store. Fill in each section of the spinner with a reward. Use tape so that you can occasionally change the awards. Be sure to vary the prizes on the spinner so that some are more desirable. You may want to have a space marked "no-win."

Establish criteria with your child, such as completing a homework assignment appropriately or finishing all of the homework tasks for the evening. When your child meets the criteria (i.e. completes the task), allow them to spin the spinner and earn the reward indicated. Be sure to use an appropriate positive statement such as, "Great job tonight! You've earned a spin on the spinner."

To phase out dependence on the spinner, change the rewards to points. These points will then accumulate towards a specific prize. Increase the number of points needed to earn the prize as your child becomes more responsible. An example of a spinner follows.

Mistakes Can Be Valuable

Learning from mistakes

Another critical tool for parents to have is to help their children learn from their mistakes. This is important because too many students are afraid to be wrong. We give our children a valuable gift by helping them understand that mistakes are valuable because they help us learn how to adjust and improve our approach as we move through a task.

Robert Brooks and Sam Goldstein in their book, Raising Resilient Children: Fostering Strength Hope and Optimism in Your Child, devote a whole chapter to learning from mistakes. They discuss various obstacles that interfere as well as some valuable guiding principles for parents to keep in mind. Following is a summary of Brooks's and Goldstein's Obstacles and Guiding Principles:

Obstacles to a Positive Outlook About Mistakes

- Temperament and biological factors

- Negative comments of parents

- Parents setting the bar too high

- Dealing with the fear of mistakes in ways that worsened the situation

Guiding Principles to Help Children Deal With Mistakes

- Serve as a model for dealing with mistakes and setbacks

- Set and evaluate realistic expectations

- In different ways, emphasize that mistakes are not only accepted but also expected

- Loving our children should not be contingent on whether or not they make mistakes

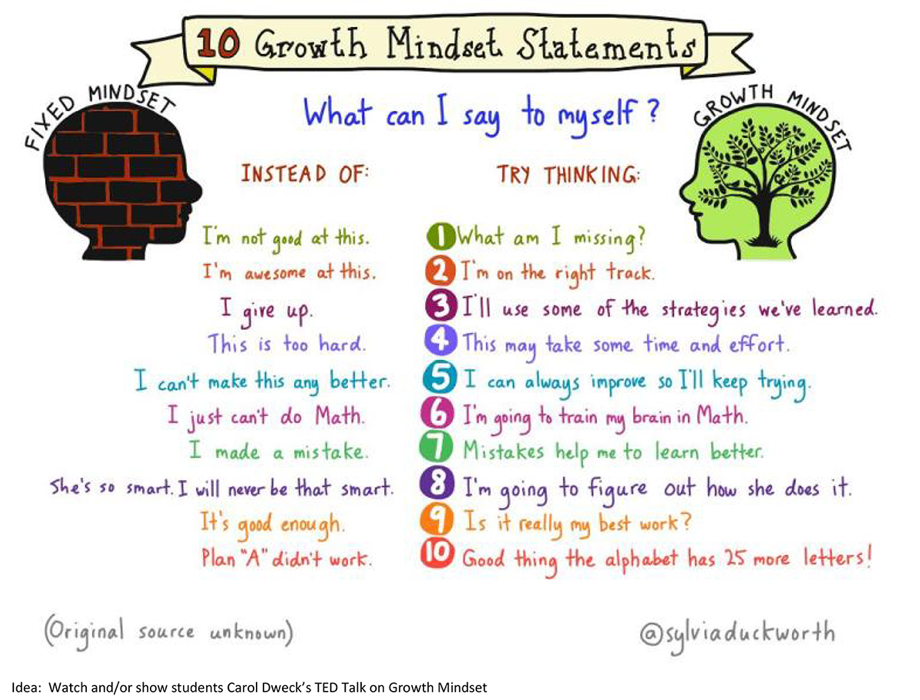

Use Growth Mindset statements (instead of Fixed Mindset statements) as in the following graphic.

References

Brooks, R. and Goldstein, S. (2002). Raising Resilient Children: Fostering Strength, Hope , and Optimism in Your Child. Amazon.

Levine, M. D. (1990). Keeping A Head In School: A Student’s Book about Learning Abilities and Learning Disabilities. Educators Publishing Service (eps.schoolspecialty.com).

Richards, R.G. (January, 2008). Being an Efficient Homework Helper: Turning a Chore into a Challenge. Written for LD OnLine (www.ldonline.org ).

Richards, R.G. (2001). L*E*A*R*N – Playful Strategies for All Students. RET Center Press (http://www.retctrpress.com/).

Richards, R.G. (2003). The Source for Learning and Memory Strategies. Pro-Ed Publishing (https://www.proedinc.com/).

Richards, R.G. and Richards, E. I. (2008). Eli – The Boy Who Hated to Write. RET Center Press (http://www.retctrpress.com/).

Author

Regina G. Richards, MA, is a board certified educational therapist and former director of Big Springs School, specializing in multidisciplinary programs for language learning disabilities. She teaches regularly at University of California Riverside Extension. She’s written several books, among them The Source for Dyslexia & Dysgraphia; The Source for Learning & Memory; Eli, The Boy Who Hated To Write; LEARN – Learning Efficiently and Remembering mNemonics, Visual Skills Appraisal2; and Classroom Visual Activities2. She is active in her local IDA branch, is a past president, and is the parent of an adult son who experiences dyslexia and dysgraphia and is currently successful in business, working with computers.

Posted in the category Learning.