- Our School

- Our Advantage

- Admission

- Elementary•Middle School

- High School

- Summer

- Giving

- Parent Resources

- For Educators

- Alumni

« Back

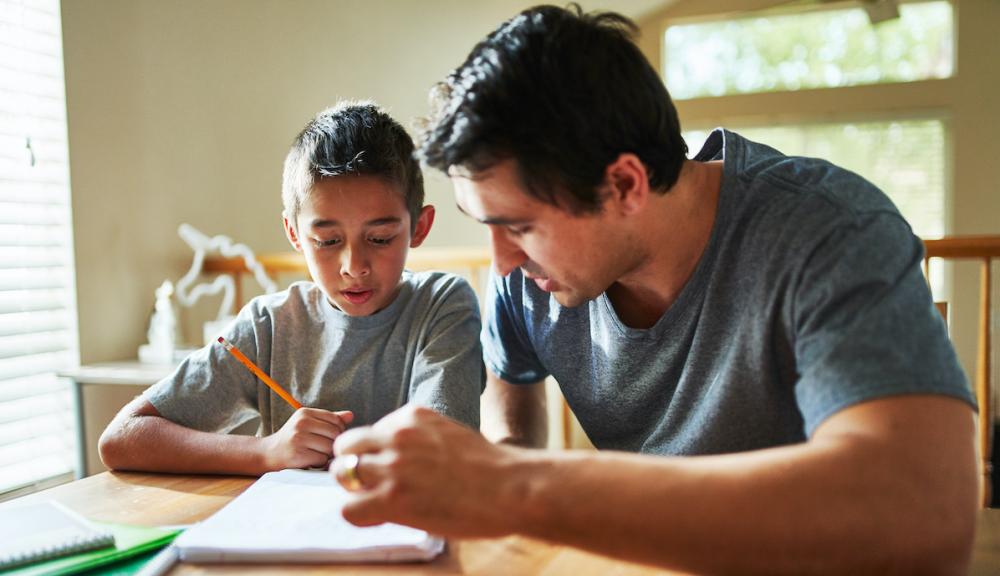

Becoming Your Child’s Learning Coach

August 12th, 2020

“Homework sucks!”

I am sure you have heard this before. So have I. I have heard it from students who would like to be doing anything other than more schoolwork. And I have heard it from parents who feel that homework is driving a wedge between them and their children. I hope to help you develop some strategies to structure at-home-learning time to keep emotions in check and to promote better learning. While parents can implement these strategies at any time, they are particularly useful when students are learning remotely with less structured learning time and without the close support of a teacher.

Provide Structure for Optimal Learning

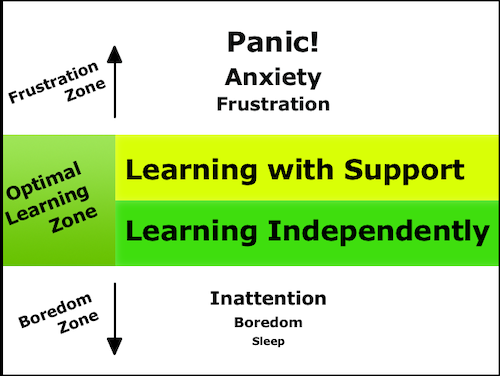

Some learning tasks can be completed with relative ease because they are clear and engaging. Students say “Homework sucks!” when they are thrown out of the optimal learning zone and into the zones of boredom or frustration.

Students become bored if tasks do not interest them or seem below their level. Even if too easy or uninteresting, the practice of learning is worthwhile. (Tip: If your student is bored, have them stand up to get a physiological boost to compensate for low demand on mental energy.)

Frustration Creates Avoidance Behavior

Frustration happens because, well, learning is hard work! It is hard mentally and emotionally. Students often become frustrated with tasks and develop the negative behavior of task avoidance. This is a regularly observed phenomenon and is studied by motivation theorists around the world. Being motivated to avoid difficult tasks is often thought of as procrastination or laziness, but it is actually a result of students not having a strong growth mindset to help them persist through difficulties or not having strong help-seeking abilities. In this post I want to focus on coaching students through their academic tasks so they achieve success through the use of strong learning habits that will provide greater confidence and fewer avoidance behaviors.

Planning Your Learning Time

Intentionally structured learning time is intended to keep the student in the optimal learning zone as much as possible. Establish set times for learning each day and make sure that you are available for some of the learning time to support your student with more difficult tasks.

At the beginning of the learning time, take 15–25 minutes to make a plan for the learning session.

Establish set times for learning each day and make sure that you are available for some of the learning time to support your student with more difficult tasks.

Students should work on the tasks that they are most interested in and are most competent with when you are the least available. More challenging tasks that cause the student frustration should be planned for a time when you are free to provide the patient guidance and support of a learning coach. In time, you can encourage your student to work on these more difficult tasks independently if you feel that they will be able to use metacognitive strategies to identify where they are having difficulties and then share those difficulties with you to debrief and receive guidance.

Creating the Learning Task List

- List all learning tasks that must be completed during the learning session.

- Put the tasks that the student feels most comfortable with at the top of the list. These are tasks that the student can do on their own without support. Acknowledge this independence to help boost their confidence and let them know you would be interested in seeing their completed work to celebrate their independent learning abilities.

- List the tasks that are challenging for the student. These are tasks that the student needs support to accomplish. They need a task attack plan! Sometimes adequate support can be delivered in helping the student structure the task. Ask the student:

- Do any of these tasks need to be broken down into smaller component parts? Writing down this plan of attack will help the student maintain effort and focus without escalating into frustration. For example, if a student is assigned an essay, have the student plan to spend 25 minutes on pre-writing with a graphic organizer, 40 minutes on writing the essay, and 10 minutes proofreading. For an elementary student, directions for completing an assignment can be confusing. Rewriting multi-step instructions as numbered bullet points can help students tackle each discrete task in the assignment.

- Are there instructional resources from the teacher that might support you with this task? Teachers have often created or curated resources and shared them through the learning management system (like Google Classroom, Blackboard, Schoology, or Canvas) or as physical resources. Students may also have other resources that they are familiar with like Khan Academy, Study.com, and ReadWriteThink.

- If the student is not aware of any resources or is still uncomfortable completing the task without support, let them know when you will be available for a set period of time to assist them. Write down the time that you will work on the activity together on the learning task list so no further mental or emotional energy is spent considering how and when that work will get done.

Task Management During Learning Sessions

To stay on task, we must help our students avoid distractions, keep their emotions in check, and not overburden them! Creating a learning environment free from distractions is hard, but by using a task management strategy you can use behavioral practice to keep distractions at bay while you are on task and then reward your student with a break to check social media, play a quick game with a younger sibling, or practice a new dance step.

One way to track time-on-task and provide regular breaks is through the Pomodoro Method. This time- and attention-management strategy has the learner set a timer to self-monitor 25-minute work sessions followed by a 5-minute break. After completing four sessions successfully, the reward is a longer break. This provides a physical and mental break at regular intervals as well as a rewards structure—strategies supported by research for all students and particularly those who experience challenges in executive function, attention, and self-regulation.

Be More Than Their Learning Coach

I hope that these tips are helpful for you as you work to help your child with their learning, but remember that you are more than a learning coach. If you are working from home, try to make time to have lunch with your kids during a longer break. And if you do need to ask a question about learning, don’t ask them about their schoolwork…ask them how their learning methods are working. Revise until you have a plan that keeps them in the optimal learning zone.

Author

Michael Hildebrandt, Ph.D., is the founder of RenewED Learning–educational consultations and coaching. He teaches courses in special education and educational psychology at Gordon College and the University of New Hampshire and has over 15 years of experience providing educational support to students and families.

Posted in the category Learning.

.jpg?v=1652115432307)