- Our School

- Our Advantage

- Admission

- Elementary•Middle School

- High School

- Summer

- Giving

- Parent Resources

- For Educators

- Alumni

« Back

Landmark’s Founding Principles: Part Three

March 15th, 2023

Problem-Solving to Meet Student Needs

By Bob Broudo

As Dr. Charles Drake conceptualized the founding of a school for students diagnosed with dyslexia and other language-based learning disabilities, many of his mission-driven founding principles and practices were already established and tested during a series of summer programs that he had overseen. All of these, and more, were woven into the fiber of Landmark well before a site for the school was identified. These principles included:

- identified student population

- ongoing faculty training

- relating science to practice

- initial teaching principles (see Landmark360 article)

- the individualized, diagnostic/prescriptive customized approach

- the daily one-to-one tutorial

- small skills-based class groupings

- the academic advisor model

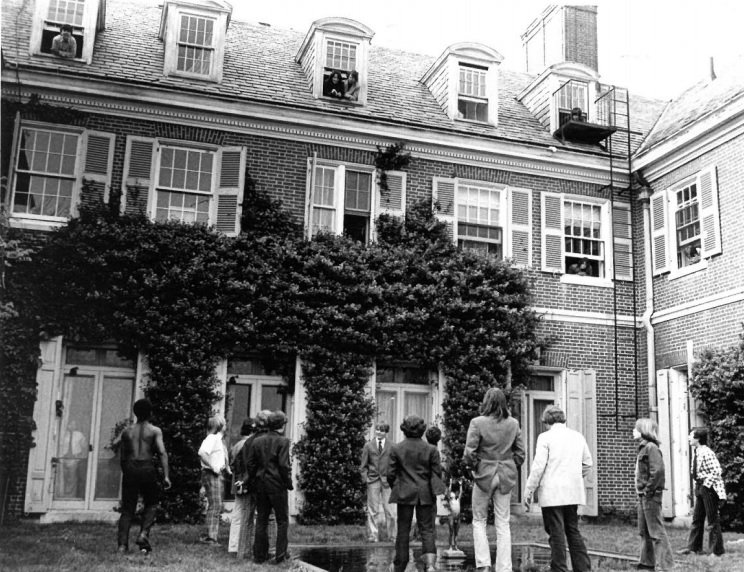

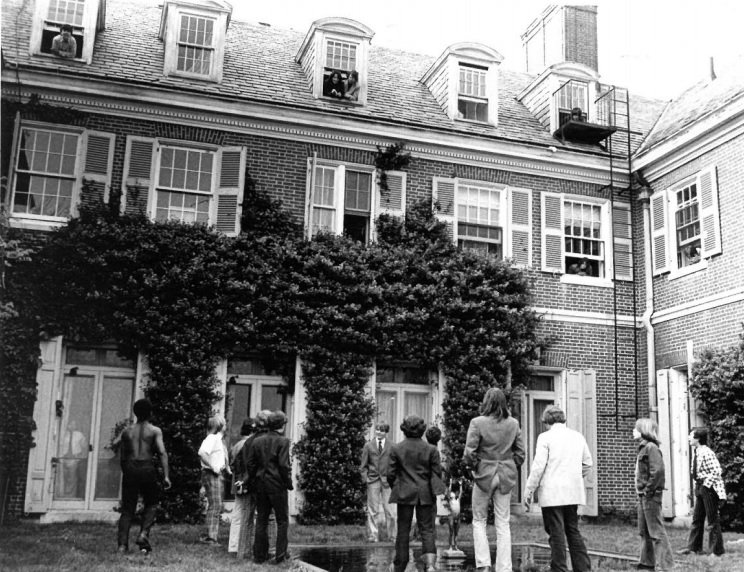

Yet evolving from the abstract to the concrete of opening a school—from the vision to execution— demanded answers to a wide array of open-ended questions, including what geographical area would be beneficial for attracting students and how to fund the purchase of a campus. Once identified, 429 Hale Street, the original and current location of Landmark School, raised even more questions. These included how to promote this brand new school and educational model to families with students who fit our identified profile; how to attract, train, and support faculty members; where to attain furniture and other teaching equipment; identify who could sand the old wooden floors, paint rooms, do electrical work, outfit the kitchen, and so on. In effect, how to convert an old summer estate into a functional school.

Perpetual Problem Solving

Interestingly, what was not actively discussed or integrated into training was a powerful strategy consistently employed to answer questions and meet challenges. Instead, this served as a thread that stitched the whole operation, methodology, and approach together from day one.

Commitment without action is meaningless, and through their deep commitment, Landmark’s constituents would come together to explore solutions to defined issues or problems. In this way, ideas would be generated, volunteers would raise hands, specific actions or activities would be identified, and results would be achieved. Through constant problem-solving, meaningful actions were created. For example, when approached, parents of summer students wrote promissory notes to a bank for a loan to purchase the property, summer teachers would leave Hebron Academy in Maine after Saturday classes, drive to Prides Crossing, and work non-stop to ready the building; a parent with the Sheraton Hotels opened a warehouse of used hotel furniture that was picked up in a U-Haul truck. Through motivation, creativity, and willingness, problem after problem was solved.

Collaborating to Meet Every Student’s Needs

Within the program, there was a daily awareness of challenging manifestations not previously discussed in training, such as students who could not grasp cause-and-effect relationships, social communication issues, visual and auditory issues, or expressive language deficits. Informally, faculty members would raise such concerns during a milkbreak meeting, Dr. Drake, Dr. Chedekol, or faculty members would suggest specific strategies, and the rule was to try these strategies and if one or more appeared effective, to share it with everyone else. Thus, identify the problem, brainstorm solutions, implement specific strategies, and share success stories. Informal “Problem Solving 101” was inherent in Landmark’s culture and a major foundational tool.

Attending the Boston University Master’s level Psycho-Educational Training Clinic brought problem-solving and clinical supervision to new heights, as these were the focus of the program. Helping public schools develop strategies to implement Chapter 766 created rich and challenging environments to implement problem-solving models. In all cases, the formula remained the same: Identify the problem, brainstorm solutions, implement the most salient ideas, observe, provide feedback, continue what is working, and repeat the cycle for continued growth.

At Landmark, the open process of problem-solving has continued to be critical. For example, to create next-step strategies for individual students or specific neurological challenges, or confronting the financial crisis in the ’90s by gathering leaders from the then four separate campuses in a carriage house in the evenings for several weeks and problem-solving how to consolidate the school to two campuses while maintaining all of its programs. The list is endless, and includes problem-solving healthy approaches to working through the pandemic while continuing to provide our educational programs for our students. Without a doubt, Landmark’s problem-solving abilities have been among its most valuable assets, have brought the school to where it is, have created openness and trust, and are simply effective and critical practices.

Landmark's Founding Principles Series

Part One: A Mission With a School

Part Two: Sharing What We Know

Part Three: Problem-Solving To Meet Student Needs

About the Author

Bob Broudo is a leader in the field of language-based learning disabilities (LBLD). He was one of the founding faculty members and then Head of School for 32 years of Landmark School, which specializes in serving students with dyslexia and other LBLD. Bob received his undergraduate degree from Bates College and his Master's degree from Boston University in Psycho-educational Training. Bob sits on several national and local non-profit and advisory boards.

Posted in the category Teaching.